In the previous post, we discussed about the 46 tombstones (47 epitaphs) mentioned by Julian James Cotton (JJC, 1905) inside the St Francis Church. Interestingly, he also records 12 Portuguese tombstones outside the church (pp. 272-273). They include 3 tombstones on the compound of the Port Office, Parade Road; 8 tombstones scattered in the streets, used as doorsteps to houses or as platforms to wells; and one tombstone in front of the Cochin Library which is illegible. The oldest of the 12 is Simeon de Miranda, who died on August 8, 1524 and according to JJC, this is also the oldest European tombstone in South India. Interestingly, when Vasco da Gama was buried inside the St Francis Church in December, 1524 (then dedicated to St Antony), Simeon Miranda who died 4 months earlier in the same year was interred somewhere in Fort Cochin, but outside the St. Francis church. Perhaps Vasco da Gama due to his legendary status was the first to be buried in the church. Remember, the oldest tombstone reported inside the church after Vasco da Gama is that of Diogo Dias and is dated to 1546 only. JJC notes that Miranda’s tombstone was brought to light while digging the foundations of the new Port office. In the introduction to his monumental work on the tomb inscriptions in Madras (1905), JJC states (p. vi): “The Cochin slab, dated 1524, recently disinterred near the new Port office, is apparently the oldest memento mori of this nation in the peninsula”. Out of the 8 tombstones scattered in the streets of Cochin, JJC identifies 6 from the 16th century, the oldest in the name of Antonio Mendes is dated to 11th December 1532, the year according to him could also be read 1522. Today, Miranda's tombstone is also conserved inside the St Francis Church along with the actual 46 tombstones. I don't think many are even aware that this rare tombstone has survived and is well preserved in Fort Kochi. Also, we do not know when exactly this 1524 tombstone was transferred to the church, but it is highly plausible that the shifting was done somewhere in the early 20th century.

The

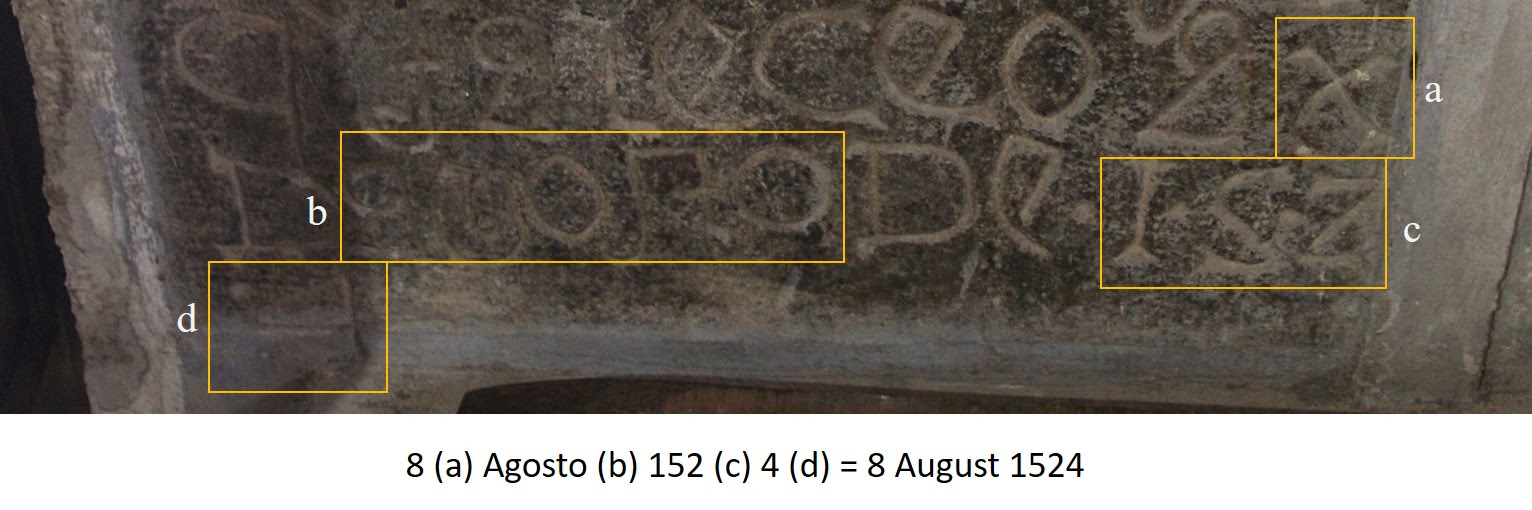

Portuguese inscription on the epitaph of Simeon de Miranda reads (JJC,

p. 272): “En esta sepultu ra iaz Simea De Miranda ffo do Fyco de Mirada

e de Dona Cezilia d’Azambuja q faleceo a 8 d’ Agosto de ISZ4”, which is

translated as: “In this tomb lies Simeon de Miranda, son of Francisco de Miranda and Cecilia d’ Azambuja who died on the August 8th, 1524.’’

The inscription on the tombstone is distributed in 9 lines and on

closer observation you can see that the year “1524” is the last word,

but inscribed in 2 lines, the numbers “152” in end of line 8 and the

number “4”, though faintly visible now, is the only character engraved

in line 9. Thanks to JJC for deciphering this rare epitaph and like he

had commented, the inscription written in a crabbed character is the

most difficult to read. Thus the arrangement of the inscription in the

tombstone is as follows:

En esta sepultu

ra iaz Simea De

Miranda ffo do Fyco

de Mirada e de

Dona Cezilia

d’Azambuja

q faleceo a 8

d’ Agosto de ISZ

4

Tombstone of Simeon de Miranda (Photo-September 2022)

Enlarged view of the 'Coat of Arms' and the section of the inscription with the date of death

In the archives of the Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds (VMIS), American Institute of Indian Studies is this beautiful image of the tombstone documented by Jose Pereira in 1968. Interestingly, the epitaph of Simeon Miranda is the only grave monument Pereira has documented from St Francis Church, which is somewhat surprising since his collections are usually rich and one would expect more tombstones photographed. Anyway, we are lucky to have this photograph where the inscriptions are very sharp and you can easily read the year 1524. The tombstone was therefore moved into the church before 1968 and since it was specifically photographed, we know the importance was well recognized.

Tombstone of Simeon Miranda (Photo-1968)

Earliest European Funerary Monuments in India

Are there any surviving European funerary monuments in India that can be dated before 1524? When you consider the different European communities who have colonized India, the Portuguese were the first to arrive (1498 in Calicut), and they got established in the subcontinent by the early 16th century. All the other European communities had their first trading posts in India from the early 17th century only. The 'East India Companies' formed initially to trade in the Indian Ocean region by the British (1600), Dutch (1602), Danish (1616) and French (1664), were ultimately meant to gain political control over the subcontinent. The chronological order of the establishment of their first factories in India would be as follows: Dutch in 1605/06 (Masulipatnam, Andhra Pradesh), English in 1608 (Surat, Gujarat), Danish in 1620 (Tranquebar, Tamil Nadu) and French in 1668 (Surat, Gujarat). This does not mean that an European (non-Portuguese) presence was absent in India before the 17th century. For instance, Dirck Gerritsz Pomp is considered the first Dutchman to visit India, who established himself as a merchant in Goa in 1568; and Jesuit priest and missionary, Thomas Stephens, is probably the first Englishman to set foot on Indian soil, who also arrived Goa in 1579. Nevertheless, I believe it is more meaningful to look for a non-Portuguese European funerary monument from the 17th century onwards- that is when they established a stronghold in the region.

Now, the more specific question would be if there are any Portuguese funerary monuments dated before 1524 that have survived in India. In the previous post, we saw 7 Portuguese tombstones inside the St Francis Church from the 16th century (1546 to 1578). JJC also lists 7 epitaphs outside the church from the 16th century (1524 to 1593), and luckily the oldest has survived and has been preserved inside the church. My understanding is that none of the remaining 6 tombstones from the Cochin streets have survived. Similarly, JJC (pp. 111-112) records 7 Portuguese tombstones from the Cathedral of San Thome, Mylapore, Chennai dated to the 16th century, but the oldest is from 1557 only. There is no denial that the death of Portuguese before 1524 are reported from Kerala, but the big question is whether their graves exist. For instance, the famous Portuguese-Galician explorer João da Nova died on 16 July, 1509 in Cochin; and Portuguese Marshal Dom Fernando Continho died in a battle fought at Calicut on 4 January, 1510, but the whereabouts of the graves are unknown. JJC concludes (Introduction, p. vi): "If we except the epitaphs at Goa, San Thome and Cochin, no monuments to the contemporaries of Camoens (i.e. 16th Century Portuguese) are traceable." In Goa, 16th century Portuguese graves are not uncommon, but reports of pre-1524 funerary monuments are rare. Historical records reveal 6 Viceroys and 2 Governors of Portuguese India were buried in Goa, but among them only one has a pre-1524 date (Afonso de Albuquerque, d. 1515, and his remains were later transferred to Portugal in 1560). So far, I have come across records of 5 Portuguese graves in Goa that can be dated before 1524:

Pre-1524 Portuguese Grave Markers in Goa

1) Captain Dom Antonio de Noronha, nephew of the famous Portuguese Admiral and Governor, Afonso de Albuquerque, who died on July 6, 1510 at the age of 24

2) Manuel, brother of Governor, Nuno da Cunha, whom was knighted by Albuquerque during the capture of Goa in 1510, died in 1511

3) Heitor Ribeiro, died in 11 November, 1515 (some read the date as 1575)

4) Afonso de Albuquerque, the second governor of the Portuguese India and often acclaimed as founder of Portuguese colonial empire in India, died on 16 December 1515

5) Gaspar d'Andrade Rego, died in 17 March, 1517

We know the location of these graves from earlier records. The Portuguese inscriptions on the tombstones of 1, 3 and 5 have been published in a late 19th century report. Nevertheless, whether any of these grave markers still survive is a matter to be investigated.

The Oldest Extant European (Non-Portuguese ) and Armenian Funerary Monuments in India:

1) English-John Mildenhall (d. June, 1614) in Agra, Uttar Pradesh

2) Dutch-Jacob Dedel (d. 29 August, 1624) in Masulipatnam/Machilipatnam, Andhra Pradesh

3) Danish-Johann Christian Lebrecht Ziegenbalg (d. 23rd May, 1718) in Tranquebar/Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu

4)

French-Jacques L'Huyer (d. 24 August, 1703) in Pondicherry/Puducherry

5) Armenian-Carapiet, the son of Mackertich of Julfa/Ispahan (d. 1557) in Agra, Uttar Pradesh

To the best of my knowledge, these are the earliest known grave markers from the European (non-Portuguese) and Armenian communities. The details are fetched mostly from works written in the late 19th to the early 20th centuries about the European and Armenian tombs in India. Luckily, the Mildenhall's (English) and L'Huyer's (French) tombstones still exist (at least their photographs taken recently are available online), but I am not aware if the original epitaphs of the other graves have survived. This in itself is not surprising when one realizes how badly sepulchral monuments are protected in India, especially if they are from abandoned foreign graveyards. Take for example the 18th century Serampore Dutch Cemetery in West Bengal. In 2021, the Archaeological Survey of India restored 61 graves from the cemetery, but only 4 epitaphs remain legible today, the oldest from 1805 and the most recent from 1964. However, in 1896, Wilson, C. R., recorded 26 tombs with inscriptions from this cemetery, the oldest is Anna Abigael Duntzfeldt, dated to 16th May, 1781. That is only 3 out of 26 epitaphs have survived in a short time span of over one century! Now if this is the condition of a late 18th century cemetery, you can expect how difficult is for a grave from the 16th or the 17th century to survive. Anyway, it would still be interesting to know if grave markers older than the ones listed above are reported. The preservation of 8 tombstones from the 16th century inside St Francis Church is therefore a remarkable achievement. Next time when you visit Fort Kochi, don’t miss the rare epitaph of Simeon de Miranda inside the St Francis church, which could be the oldest surviving European grave marker in South India if not the whole country.

No comments:

Post a Comment