JEWISH MONUMENTS & ARTIFACTS OF KERALA

The most important Jewish heritage structures in Kerala are the synagogues (Juda Palli in Malayalam), cemeteries and residences.

A. Synagogues

Today, there are 35 synagogues in India and 7 of them are in Kerala. The architectural style of Kerala synagogues differs from those in the west. These synagogues are strongly influenced from earlier Hindu religious buildings on its design and construction. They are characterized by high slope roofs, thick laterite-stoned walls, large windows and doors, balcony and wood-carved ceilings. A Kerala synagogue consists of a ‘Gate House’ at the entrance that leads through a Breezeway to the Synagogue Complex. The synagogue complex is made of a fully enclosed Azara or Anteroom and a double-storeyed sanctuary-the main prayer hall. Inside a typical double-storeyed sanctuary of a ‘Kerala Synagogue’ are:

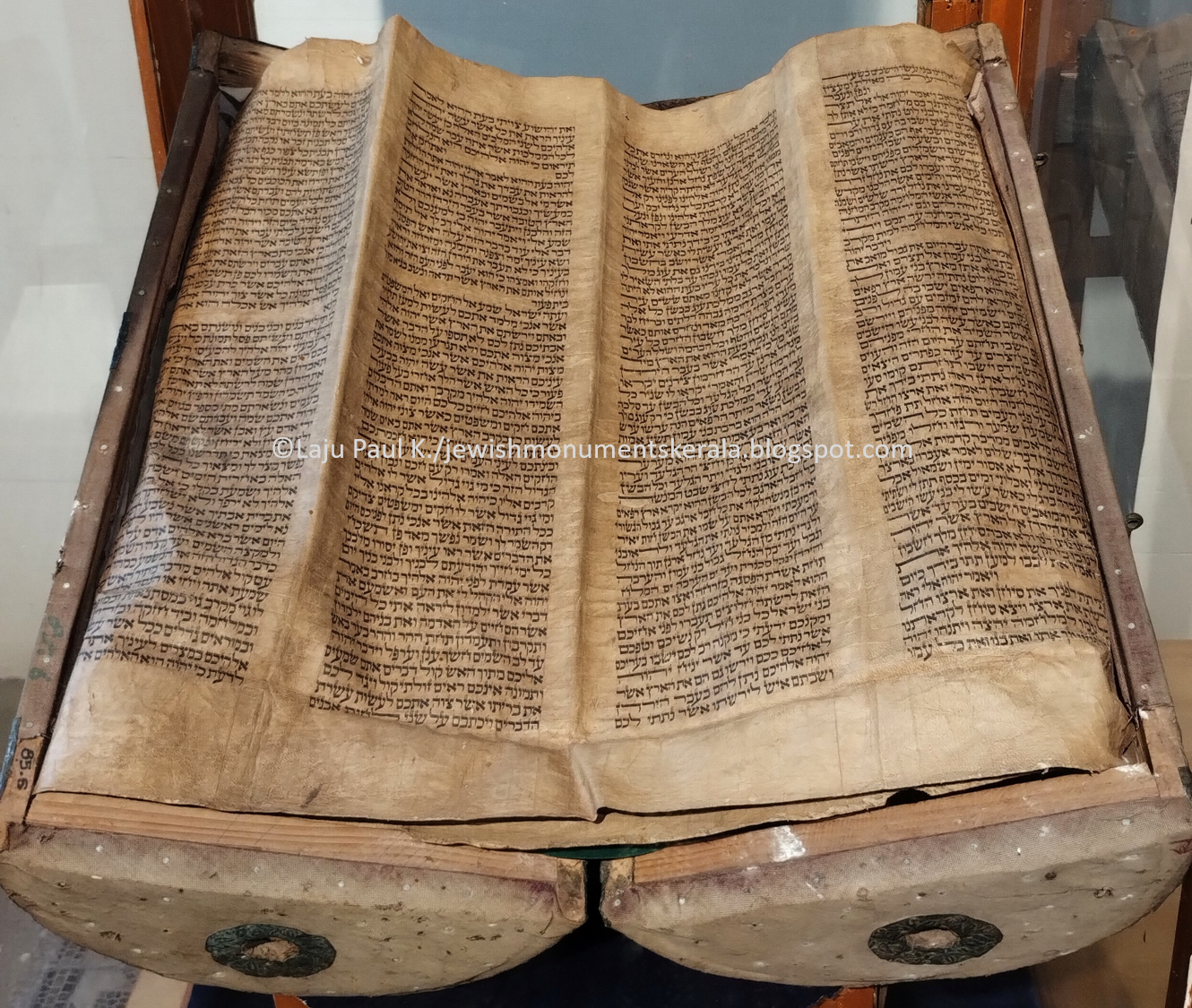

1) A Tebah/Bimah: Located at the center of the sanctuary, Tebah is usually an elevated wooden platform or pulpit from which Torah, the holy book of Jews is read. 2) A Heichal (Ark): Represents the altar. It is a chest or cupboard in the synagogue where the Torah scrolls are kept. It is usually carved intricately and painted/gilded with teak wood. Unlike in the European Synagogues, where the ark is placed on the eastern wall, the synagogues in Kerala have the arks on the western wall facing Jerusalem. 3) A Balcony/Second Tebah: It is unique to the synagogues of Kerala. The balcony has two portions one for men and the other for ladies. Women’s seating area is placed directly above the azara. 4) A Staircase: Leads to the balcony and is generally spiral in shape and made of wood. At times there are two staircases, one for men from the main hall inside the synagogue and the other for the ladies from a staircase room outside the synagogue; 5) A Jewish School: Is actually a classroom for Jewish children usually located behind the women’s section on the first floor.

B. Cemeteries

Resting place of ancestors means a lot to the Jewish community. Sometimes they even carried tombstones from their old settlements while migrating to a newer place. The oldest Jewish tomb in India (dated 1269 AD) preserved in front of Chendamangalam synagogue is one such transferred from Kodungallur. Unlike Christian tombs in Kerala with Malayalam and English engravings, the Jewish graves have mostly Hebrew inscriptions. The Jewish year can be converted into modern Gregorian date if one can read the Hebrew letters. ‘Reading Hebrew Tombstones’ is an interesting site to read the Jewish tombs.

C. Jewish Residences

Today, most of the early Jewish homes sold to non-Jews are substantially modified or refurbished. However, there are a few features that still make them identifiable. Sometimes you can trace Jewish symbols like Menorah (candlestick) and Magen David (Star of David) on the walls, windows and roof tops. For example, a few residences in Mattancherry still maintain the Star of David (Magen David) despite being converted into shops or warehouses. The best way to locate the home of a residing Jew is to look for the Mezuzah on the door post. Nailed to the doorpost of a Jewish home, Mezuzah is a small container made of wood, plastic or metal having a piece of parchment with the most important words from the Jewish Holy Book, Torah. It is customary among religious Jews to touch the mezuzah on entering or leaving the home. A few homes in the Synagogue Lane of Mattancherry with mezuzah are the residences of the remaining 9 Paradesi Jews.

The Jewish monuments and artifacts I will be discussing in this blog are:

I Synagogues

1. Pardesi Synagogue, Mattancherry (1568)

2. Kadavumbagam Synagogue, Mattancherry (1130 or 1539)

3. Thekkumbagam Synagogue, Mattancherry (1647, only the building site known)

4. Kadavumbagam Synagogue, Ernakulam (1200)

5. Thekkumbagam Synagogue, Ernakulam (1200 or 1580))

6. Paravur Synagogue (750 or 1164 or 1616)

7. Mala Synagogue (1400 or 1597)

8. Chendamangalam Synagogue (1420 or 1614)

(The various speculated dates of establishment in parenthesis are taken from www.cochinsyn.com, coutesy Prof. Jay A. Waronker)

II Cemeteries

1. Pardesi Jewish Cemetery, Mattancherry

2. Malabari Jewish Cemetery, Mattancherry

3. Old Jewish Cemetery, Ernakulam

4. New Jewish Cemetery, Ernakulam

5. Paravur Jewish Cemetery

6. Mala Jewish Cemetery

7. Chendamangalam Jewish Cemetery

III Jew Streets

1. Jew Street Mattancherry (Jewish residences with Mezuzah and Magen David)

2. Jew Steet, Ernakulam (today all shops in non-Jewish hands)

3. Jew Street, Paravur (Twin Pillars)

4. Jew Street, Mala (Gate House and Breezeway of synagogue turned into shops)

5. Jew Street, Chendamangalam (used to be a Jewish Market or Judakambolam)

6. Jew Street, Calicut (identified in July 2011 as Jootha (Jew) Bazar)

IV Other Monuments & Artifacts

1. Tomb of Sarah (1269 AD), Chendamangalam

2. Kochangadi Synagogue Corner-stone, Mattancherry

3. Jewish Children’s Play Ground, Mattancherry

4. Clock-Tower, Mattancherry

5. Sarah Cohen’s Embroidery Shop, Mattancherry

6. Jew Hill/Judakunnu/Jewish Bazar, Palayur

7. Jew Tank/Judakkulam, Madayi

8. Koder House, Fort Kochi

9. Grand Residencia, Fort Kochi

10. Jewish Summer Resorts, Aluva

11. Jewish Copper Plates, Mattancherry

12. Syrian Copper Plates, Kollam

13. Torah Finial, Palayur

V Lost Jewish Colonies

1. Kodungallur (Thrissur)

2. Palayur (Thrissur)

3. Pullut (Thrissur)

4. Kunnamkulam (Thrissur)

5. Saudhi (Ernakulam)

6. Tir-tur (Ernakulam)

7. Fort Kochi (Ernakulam)

8. Chaliyam (Kozhikode)

5. Pantalayani Kollam (Kozhikode)

9. Thekkepuram (Kozhikkode)

10. Muttam (Alappuzha)

11. Kayamkulam (Alappuzha)

12. Dharmadom (Kannur)

13. Madayi (Kannur)

14. Quilon (Kollam)

15. Pathirikunnu, Krishnagiri (Waynad)

16. Anchuthengu (Thiruvananthapuram)